The Philadelphia Chromosome

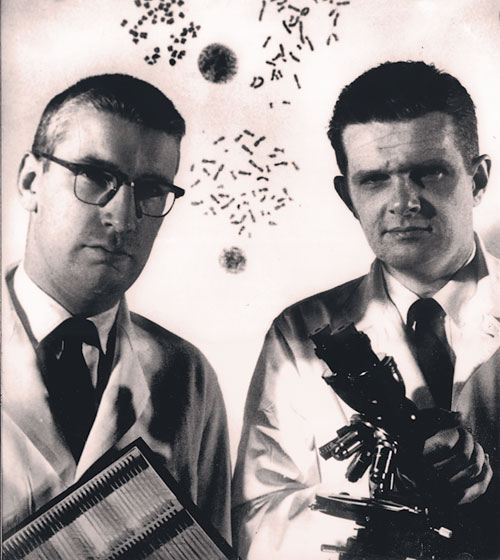

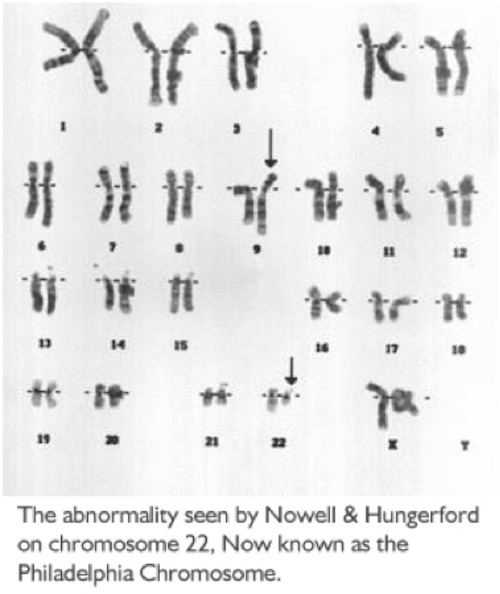

Cells in the body most often hold 23 pairs of chromosomes. One day, Drs. Peter Nowell and David Hungerford, two Philadelphia researchers, were experimenting with cells from many types of leukemia. They noticed chromosome number 22 looked smaller than normal on the cancer cells of two people with CML (Chronic Myeloid Leukemia). With the far less sophisticated techniques of the time, they were not able to tell what happened to the material missing from the small chromosome.

Nowell and Hungerford published their research in 1960, that described the abnormal finding. They studied further and the smaller-than-normal chromosome 22 was found in 9 out of 10 patients with CML. A group in the United Kingdom confirmed the finding and it was then named the Philadelphia Chromosome, for the city in which it was found. Nowell and Hungerford proved that this genetic change was needed for the growth of CML - a novel and often unaccepted concept at that time.

In 1972, one more researcher Janet Rowley, MD, found the missing piece of chromosome number 22 attached to chromosome number 9. This was the finding of the first known chromosomal translocation (changing locations). The 9;22 translocation is found on the leukemic cells of more than 95% of patients with CML. As more genetics studies were done, it was learned that the gene abl (pronounced "able"), in most cases found on chromosome 9, had attached itself to the gene bcr (pronounced "b-c-r") on chromosome 22. The bcr-abl gene encodes a protein (called tyrosine kinase), whose activity results in too many stem cells changing into white blood cells, leaving a shortage of other cell types. This genetic change to bcr-abl occurs during a person's lifetime and is not passed on to future generations or passed down from parents.

Flash forward to the 1990s, when a group of researchers, led by Dr. Brian Druker in Oregon, began work on a medication known as STI-571. This would become the first medication to exactly target cancer cells – in this case, the target is BCR-ABL. The first group of patients involved in studies of this medication, later named imatinib (Gleevec), had failed other treatments and joined the STI-571 trial as a last effort. Nearly all the patients saw their white blood cell counts return to normal within a few weeks of starting the therapy. This medication – the result of nearly 40 years of research – would change the future of cancer care and how researchers look at treatments.

Imatinib was the first of many targeted therapies that have changed how we treat many cancers – and it all started with an interesting finding in a small lab in Philadelphia.