Aerobic Exercise Program During and After Cancer Treatment

Disclaimer: Exercise is safe for most people during cancer treatments, but it is important to check with your provider before starting an exercise program. There may be some days during your treatments when you shouldn't exercise.

Why should I exercise?

Exercise is an important part of cancer care during and after treatment. It has many benefits and should be a part of your treatment plan no matter your type or stage of cancer.

Exercise is safe and can help with many things during and after cancer treatment like:

- Poor sleep.

- Low energy (fatigue).

- Feeling nervous or sad.

- Weakness.

- Fitness.

- Pain.

- Thinking more quickly.

For people with breast, endometrial, prostate, or colon cancer, exercise may help prevent your cancer from coming back.

What Kind of Exercise Should I Do?

There are two main kinds of exercise: aerobic and strengthening.

Aerobic exercise involves any activity that raises your heart rate over a sustained period.

Types of aerobic exercise are:

- Walking.

- Biking.

- Gardening.

- Jogging.

- Dancing.

- Jumping rope.

- Swimming.

Strengthening exercises are any exercises that cause your muscles to feel resistance. This stimulates muscle growth, improves strength, and increases muscular endurance.

Types of strengthening exercises are:

- Lifting weights.

- Using your body weight as resistance (lunges, squats, sit ups).

- Using resistance bands.

- Pilates.

- T'ai Chi.

- Some types of yoga.

See this article for pictures of strengthening exercises.

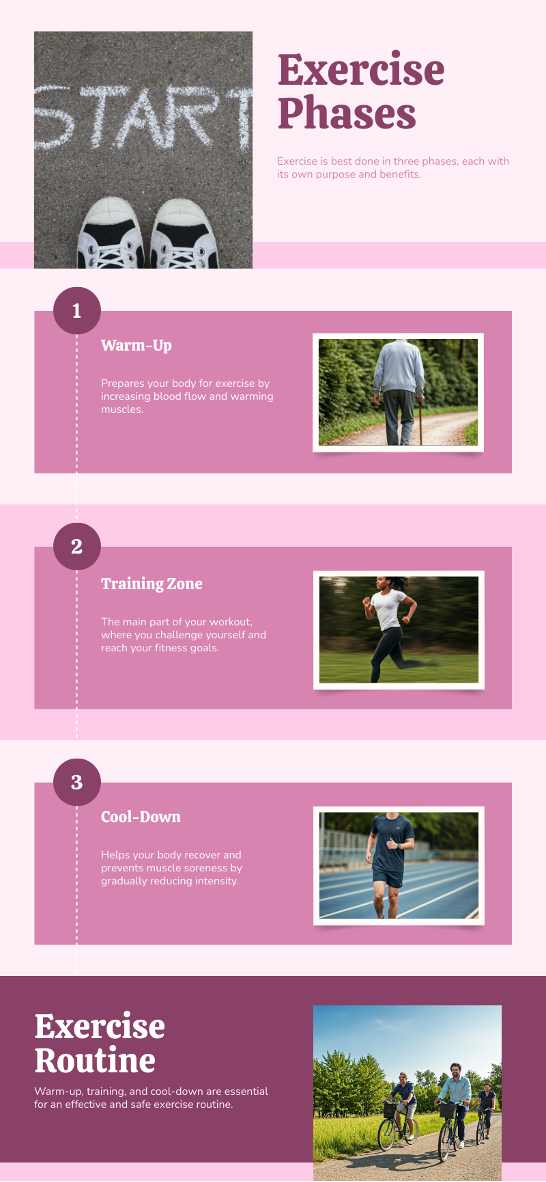

Aerobic Exercise Components

Warm-Up

Warming up before exercise is important for everyone, especially if you are new to exercising, have heart problems, or are over 55. A good warm-up helps your body get ready by slowly raising your heart rate and body temperature. It also prepares your nerves and muscles to move more easily and may help prevent injuries.

Examples of a warm-up:

- Walk for 5 minutes at a slow, easy pace. On a scale of 0-10, with 0 meaning no effort and 10 meaning maximal effort, an easy pace is about 1-2.

- Bike slowly for 5 minutes at an easy pace.

Aerobic Exercise – Training Zone

Intensity is one of the most important factors that will determine how much you improve. To gain the benefits of exercise, you have to "overload" or push your body. It’s important to do this slowly to prevent injury. There are a number of ways to know if you are working hard enough to gain the benefits. Measurements of intensity or workload include the Borg Rating of Perceived Exertion (RPE) scale, heart rate response, or the talk test.

Borg Scale of Perceived Exertion

The Borg Scale of Perceived Exertion is a common tool to determine the amount of effort you are expending. When exercising, take notice of how tired your muscles are, how quickly or heavily you are breathing, and how fast your heart is pumping. Taking all of these things into consideration, look at the chart and choose a number or phrase that reflects your effort.

If you haven’t been exercising or are experiencing a lot of side effects from treatment, aim to work at a rating of 9-11 “Very Light to Light work.” Once you work up to walking for 20 continuous minutes at this level, gradually increase your intensity to 11-13. You can do this by walking or biking faster, incorporating small hills in your workout, or swinging your arms during walking.

You can also use a modified version of this scale that rates effort from 0-10. 0 represents rest while 10 represents maximal effort. If you are new to exercising, start at a rating of perceived exertion (RPE) of 2 and progress to a 3-4. Remember to consider how fast you are breathing, how hard your heart is pumping, and how hard your muscles are working when determining your rating.

Heart Rate

Monitoring your heart rate is another way to determine the intensity or how hard you are working.

Heart rate monitoring is a more precise way to determine if you are working “hard enough” to gain benefits compared to using the Borg Scale. However, both are effective, so choose the one that works for you.

To determine how high your heart rate should be during exercise, you can use the following equations or online calculator to calculate a heart rate range. Once you calculate this range, try to keep your heart rate in that zone to reap the benefits.

1. Subtract your age from 220. This is your maximum heart rate.

- For example, if you are 60 years old, your maximum heart rate would be (220-60) = 160 beats per minute.

2. After sitting for a few minutes take your heart rate.

- Put your pointer finger and middle finger at the top of your thumb.

- Slide these two fingers down your thumb until you get to your wrist.

- Count how many beats you feel under your fingers for 60 seconds or 1 minute. This is your resting heart rate. Most people will have a resting heart rate between 60 and 100 beats per minute.

- The next step is to use your resting heart rate to determine the heart rate range you should be in while exercising to gain the benefits. Use the following equation to determine the heart rate range you will aim for while exercising. You can also try this online calculator.

- If you haven’t exercised before, haven’t exercised in a while, or experienced side effects from your cancer treatment, start in the very light or light range of 20-39%.

(HR max – HR rest) x .25 + HR rest = low end of training zone

(HR max – HR rest) x .39 + HR rest = high end of training zone

For example, I am a 60-year-old woman who has finished treatment for colon cancer. I talked to my provider about exercise and she says that I can start a program.

My maximum heart rate is: 220-60 = 160 beats/minute.

I count 78 beats on my wrist in 1 minute. This is my resting heart rate.

My training zone is:

(HR max – HR rest) x .25 + HR rest = low end of training zone

(160-78) x .25 + 78 = 100.5 beats per minute

(HR max – HR rest) x .39 + HR rest = high end of training zone

(160-78) x .39 + 78 = 113 beats per minute

After my 5-minute warm-up, I will walk faster. When I walk faster, I will take my heart rate. My goal is to have my heart rate between 100 beats/minute and 113 beats/minute. If my heart rate is between these numbers, I am walking at a good pace to get the most out of my exercise program.

If my heart rate is less than 100 beats/minute when walking, I should Walk Faster.

If my heart rate is more than 113 beats/minute when walking, I should Walk Slower.

You should not use this heart rate equation if you take a class of medications called Beta-Blockers. These medications are commonly used for people with heart conditions such as a heart attack, heart failure, or a-fib. Instead, use the Borg Scale or the Talk Test.

Examples of Beta Blocker medicines are: Tenormin, Cardicor, carvedilol, Lopressor, Inderal

Talk Test

Another easy way to determine if you are working hard enough is the talk test. When you are walking you should feel a little breathless and you may sweat. You should aim for a speed or pace that allows you to talk, but not sing. When you talk, it should be “breathy.” You should be able to get a few words out before needing to take another breath. If you are able to sing, then your intensity is too low, and you should quicken your pace.

Cool Down

At the end of your exercise, you need to cool down your heart, body temperature, and muscles. You should walk slowly for 5 minutes before stopping. This is one way to reduce the risk of dizziness and feeling faint after exercising. If you have a heart condition, your provider may ask you to cool down for more than 5 minutes.

How many days each week should I exercise?

During treatment, you should try to do some activity most, if not all days of the week. You might start with 3-5 minutes in the “training zone,” adding in 1-5 minutes per week to work yourself up to 20-30 minutes at one time. For some, this may be too aggressive, so think about getting 20-30 minutes of walking done each day by breaking it up into smaller pieces. For example, walk 5 minutes, rest 5 minutes, and repeat. You can also spread the exercise up throughout the day by exercising a few minutes in the morning, around lunchtime, and then again late afternoon. If you have not exercised before, or you are having a lot of side-effects from treatment, you should start more slowly or consider seeking out the expertise of an oncology exercise specialist.

Are there different exercise recommendations depending on what symptoms I have?

Yes! There are some symptoms associated with cancer that benefit from a certain dose or amount of exercise. See the recommendations below from The American Cancer Society American Cancer Society nutrition and physical activity guideline for cancer survivors.

Cancer-related fatigue

Cancer-related fatigue (CRF) is a sense of physical, emotional, and/or cognitive (thinking) tiredness that results from cancer or cancer treatments. The tiredness experienced is not related to the amount of effort you expend or the activities that you participate in and isn’t fully relieved by resting.

Fatigue impacts nearly everyone going through cancer treatments and sometimes extends beyond treatment. While it seems contradictory, exercising can help to combat fatigue.

The recommended amount of exercise to manage fatigue is:

- Aerobic exercise 3 times per week.

- Working up to 30 minutes each session.

- Moderate intensity.

*There is also a recommendation for strength training to combat fatigue. Refer to our article on Strengthening During and After Cancer.

Health-Related Quality of Life

To improve quality of life during and after cancer treatments, the recommendation for aerobic exercise is:

- Aerobic exercise 2-3 times per week.

- Working up to 30-60 minutes.

- Moderate to vigorous intensity.

*There is also a recommendation for strength training. Refer to our article on Strengthening During and After Cancer.

Physical Function, Anxiety, or Depression

Similar exercise prescriptions are recommended to improve your ability to function (walk, shower, and do daily activities) or to improve feelings of anxiety or depression. To improve these symptoms during or after cancer treatments it is recommended to:

- Perform aerobic exercise 3 times per week

- Working up to 30-60 minutes per session

- Moderate to vigorous activity

*There is also a recommendation for strength training. Refer to our article on Strengthening During and After Cancer.

Chemotherapy and Exercise - Important Considerations

If you are receiving chemotherapy to treat your cancer, you should talk to your provider about exercise. Each type of chemotherapy is different in how it affects your body. Some days, your provider might ask you not to exercise because of low blood counts or fever. Or, they may ask you to stay active, but reduce the intensity that you are exercising.

Make it a point to discuss exercise with the oncology team at your next visit.

Some side effects of chemotherapy that may affect your ability to exercise are:

Anemia

- Anemia means that you have low red blood cells or hemoglobin. Hemoglobin carries oxygen through your body, so if your levels are low due to treatment, you likely feel tired and may get short of breath with activity.

- Many people can continue to exercise while anemic by lowering the intensity or duration of the activity. Your physician may ask you to hold your activity if your hemoglobin levels are below 8 mg/dL.

- If you have heart disease or are older, consult with your physician about exercise when you are anemic.

Low platelet counts (Thrombocytopenia)

- Chemotherapy may lower your platelet count.

- Platelets help to stop bleeding.

- You may bruise or bleed easily if your platelets are low.

- If you have any problems with balance, feel unsteady, or have feelings of dizziness, you should not exercise with low platelet counts.

- There are days when you should not do strengthening exercises when your platelets are low.

- Talk to your provider about activity suggestions when your platelets are low.

Tingling in your hands or feet (peripheral neuropathy)

- Some types of chemotherapy can cause tingling in your hands and feet.

- Tingling may affect your balance.

- Talk to your provider about exercise with peripheral neuropathy so that you can learn to do it safely.

- Find a physical therapist who understands chemotherapy and peripheral neuropathy. They may be able to help with the tingling feeling as well as improve your balance.

Food and Weight Loss

- If you have lost weight during treatment, you have also lost muscle.

- Exercise can help you get stronger.

- Talk to a dietitian about what foods you should eat to help you have enough energy to exercise and to help regain any muscle you lost.

Radiation Therapy and Exercise

Radiation therapy is a common treatment for cancer. Most people who get radiation feel tired (fatigue). Exercise can help you manage fatigue and give you more energy.

OncoLink has a large section on cancer-related fatigue, with helpful tips and information.

Radiation and the sun

You are more likely to get a sunburn during and after radiation therapy. Talk to your provider about skin protection. You may want to exercise in the morning or in the early evening so that you are less likely to get a sunburn.

If you got whole-body radiation therapy, you should be careful about exercising in hot weather. Your body may have trouble getting rid of the heat you make during exercise (sweating), which can be dangerous. Dress in light clothes and exercise in the morning or early evening. Talk to your provider about when and how you should exercise.

Your Bones and Cancer

Some cancers affect the bones in the body, making them weak. Other times, the treatment you get for cancer can cause bones to weaken. Exercise, if done right, can help to strengthen your bones.

Cancers that MAY affect your bones are:

- Multiple myeloma.

- Lung cancer.

- Sarcoma.

- Breast Cancer.

- Prostate Cancer.

- Testicular Cancer.

It is important that you talk to your provider about the health of your bones.

Your provider may tell you it is safe to exercise.

Your provider may ask you to stop exercising until after treatment has ended.

Your provider may tell you not to use heavy weights for strengthening if you have cancer in your bone and you are at a higher risk for fracture.

See this section on OncoLink for recommendations for strengthening or resistance training.

Safety with Exercise - Important

- Talk to your provider BEFORE starting an exercise program.

- You should not exercise if you:

- Have pain or discomfort anywhere above your waist while exercising (chest pain, left arm pain, jaw pain, neck pain or nausea).

- Feel dizzy or lightheaded.

- Have experienced a recent fall or near fall.

- Feel unsteady.

- Bruise easily due to low platelet counts.

- Have a fever.

- Have pain while walking.

- Have pain with sneezing, coughing or laughing.

- Have numbness or tingling that hasn't been evaluated by your medical team or physical therapist.

- Have significant amounts of diarrhea.

Quick Tips for Exercise

- Talk to your provider about an exercise program.

- Do something that you find is fun and makes you happy.

- Find a partner.

- Consider group programs that provide exercise and a source of community support.

- Find an exercise specialist who has additional training in working with people who have cancer.

- Arm yourself with information about the benefits of exercise during and after cancer treatment.

- Find a place to exercise that is close to where you live. The closer it is, the more likely you will exercise!

- Listen to music while you exercise.

- Do different types of exercise to train different parts of your body and to avoid boredom.

- Set goals that you can reach.

- Be kind to yourself.