Intensity-Modulated Radiation Therapy (IMRT)

Intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) is a type of external radiation. IMRT is one of the most common types of radiation therapy for many kinds of cancer.

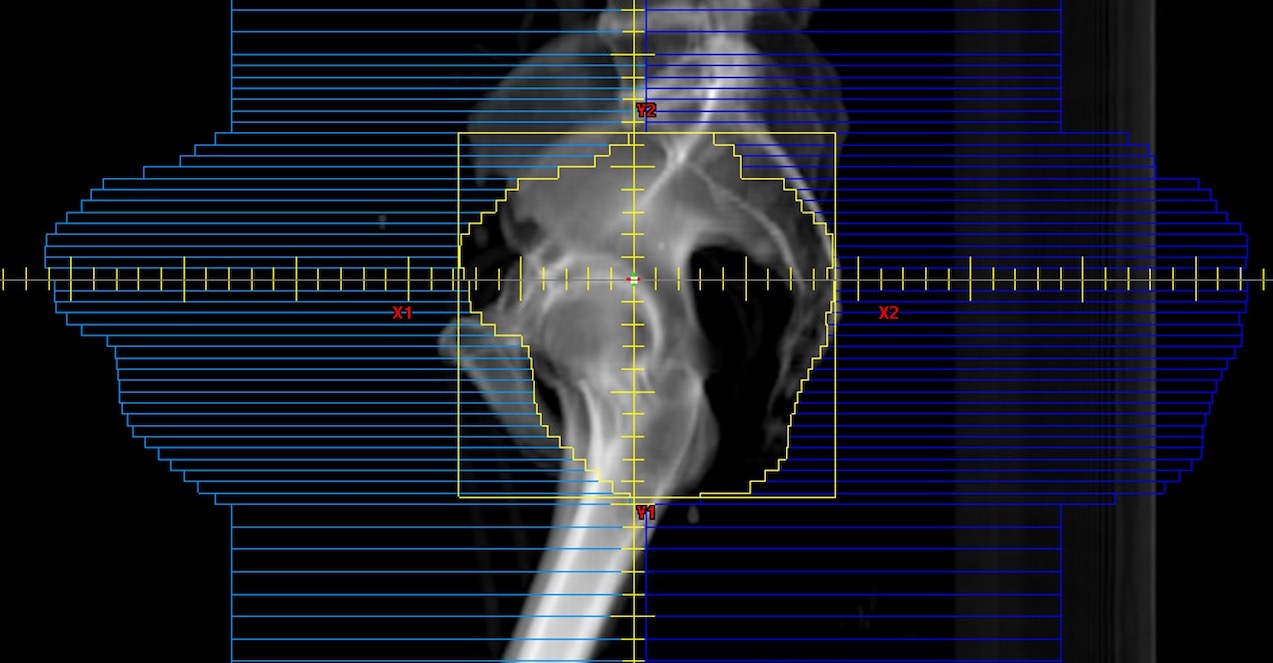

Before treatment, a radiation oncologist uses a CT scan, and sometimes an MRI or PET/CT, to make a 3D image of your body on a computer. This 3D image allows multiple radiation beams to target a tumor and to better shape the radiation to the tumor. It also reduces the amount of radiation delivered to nearby healthy tissue. With this 3D image, the radiation oncologist can plan treatment beams coming from different angles outside of the body so that they all come together inside the body at the target (tumor).

IMRT is a form of 3D planning. IMRT lets your radiation team shape each treatment beam using small blocks, called “leaves.” The tool used is called a multileaf collimator (MLC). The MLC tells the small leaves to move across the beam’s path at different speeds and patterns. The leaves sometimes do not move while the beam is on. Parts of the radiation beam are selectively blocked for part of the treatment time. Certain parts of the beam give higher-intensity radiation that results in a higher dose. Other parts of the beam give lower-intensity radiation that results in a lower dose. In other words, the intensity across the beam can be modulated (changed). This is how intensity-modulated radiation therapy got its name.

This method can create precise delivery of radiation within the body. The result is a dose of radiation that can be higher in certain areas, lower in others, and even curve around nearby organs.

Like most other radiation treatments, IMRT is given as fractionated radiation, meaning that the total dose of radiation is given in many small daily, or twice-daily, treatments. Treatments are given over the course of many weeks.

When is IMRT used?

Some of the cancers IMRT is used to treat are:

- Prostate cancer.

- Head and neck cancers.

- Gastrointestinal (GI) cancers.

- Gynecologic cancers.

- Brain tumors.

IMRT is most often used when a tumor partly surrounds or is very close to a healthy part of your body that cannot handle the full dose of radiation being given to the tumor. When the tumor is not near sensitive areas, IMRT may not be needed. Talk with your radiation team to see which type of treatment is best for you.

Is IMRT right for me?

Because the radiation beams are coming at the tumor from different angles, a low-dose ‘bath’ of radiation is made just outside the tumor. The long-term impact on the low-dose region is not known, but your radiation team always works to lower radiation exposure to normal tissue. Spreading out low doses of radiation may cause acute or late radiation side effects, based on which organs are in the low-dose region.

IMRT can also cause ‘hot spots’ or ‘cold spots’ of radiation. Hotspots in organs can put the patient at higher risk for side effects and cold spots can mean the tumor is not getting enough radiation to control the cancer.

Planning and giving an IMRT treatment takes longer than some other radiation treatments. As with all radiation treatments, patients must be able to stay comfortably still during the whole time the beam is on. Even small movements by the patient during treatment can change how well IMRT works.

Sometimes treatment needs to be done quickly to treat the cancer or manage symptoms. Some patients may be unable to stay still during radiation because of pain or mobility (movement) issues. In these cases, IMRT would not be the best choice.

There are benefits of IMRT:

- The greater amount of low-dose radiation to nearby areas in the body.

- Possible added toxicity.

- Longer treatment times.

- The cost.

Talk with your radiation care team about your diagnosis and whether IMRT should be a part of your treatment plan.