Liver Cancer: Staging and Treatment

What is staging for cancer?

Staging is the process of learning how much cancer is in your body and where it is. Tests like biopsy, angiogram, bone scan, ultrasound, PET scan, CT, and MRI may be done to help stage your cancer. Your providers need to know about your cancer and your health so that they can plan the best treatment for you.

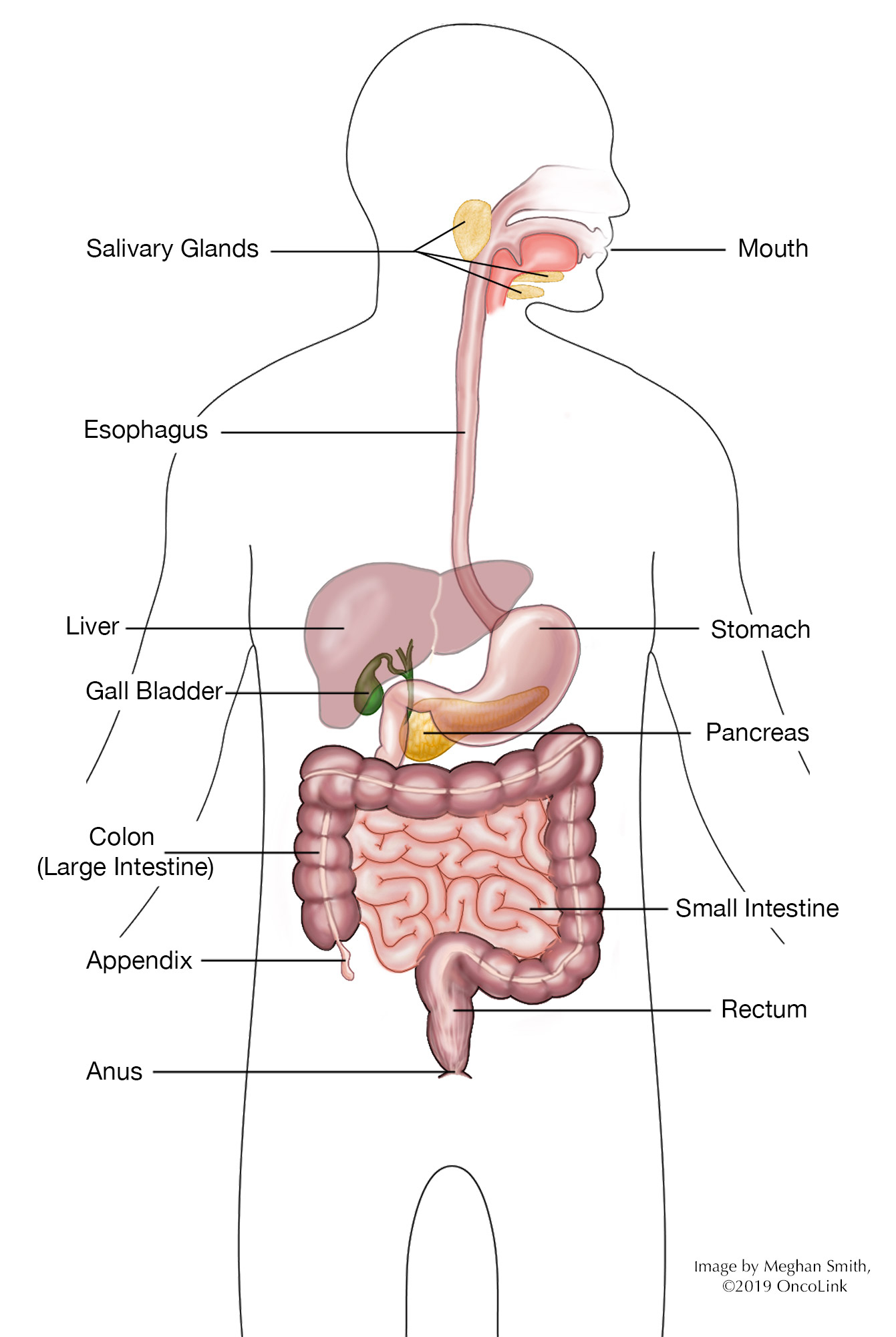

There are a few kinds of liver cancer, named for the type of cell that the cancer starts in.

- Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC): Starts in cells called hepatocytes. This is the most common type of liver cancer.

- Hemangiosarcomas: A rare cancer that starts in the blood and lymph vessels.

- Hepatoblastoma: A rare cancer that happens in very young children.

- Fibrolamellar liver cancer: A rare cancer that happens in teens and young adults with no history of liver disease. Learn more about childhood liver cancers here.

There are a few staging systems for liver cancer.

- The Child-Pugh score helps to figure out how well your liver is working. It shows how severe the liver disease is. Points (from 1-3) are given for: Evidence of ascites (fluid in the belly), encephalopathy (confusion), bilirubin and albumin levels, and bleeding time. These points are combined to give a total score from 5-15. Based on the score, a letter grade of A, B, or C is given. A score of A shows good liver function. A score of C means that the liver is not working well.

- The Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (CLIP) staging system looks at how well your liver is working (using the Child-Pugh score) and other factors.

- The Milan and USCF systems may also be used for staging, especially if you are being tested for liver transplant.

- The AJCC system is the most common way to stage liver cancer. It uses the “T-N-M” system, described below. This article will focus on this system.

Cancer staging looks at the size of the tumor and where it is, and if it has spread to other organs. It has three parts:

- T-describes the size/location/extent of the "primary" tumor in the liver.

- N-describes if the cancer has spread to the lymph nodes.

- M-describes if the cancer has spread to other organs (called metastases).

Your healthcare provider will use the results of the tests you had to figure out your TNM result and combine these to get a stage from 0 (zero) to IV (four).

How is liver cancer staged?

The AJCC system for staging for liver cancer is based on:

- The size of your tumor seen on imaging tests and what is found after surgery (if you have had surgery).

- If your lymph nodes have cancer cells in them.

- Any evidence of spread to other organs (metastasis).

The staging system is very complex. Below is a summary of the staging. Talk to your provider about the stage of your cancer.

Stage IA (T1a, N0, M0): A single tumor 2 centimeters (cm) or smaller that hasn't grown into blood vessels (T1a). It has not spread to nearby lymph nodes (N0) or to distant sites (M0).

Stage IB (T1b, N0, M0): A single tumor larger than 2cm that hasn't grown into blood vessels (T1b). The cancer has not spread to nearby lymph nodes (N0) or to distant sites (M0).

Stage II (T2, N0, M0): Either a single tumor larger than 2 cm that has grown into blood vessels, OR more than one tumor but none are larger than 5 cm (T2). It has not spread to nearby lymph nodes (N0) or to distant sites (M0).

Stage IIIA (T3, N0, M0): More than one tumor, with at least one tumor larger than 5 cm (T3). It has not spread to nearby lymph nodes (N0) or to distant sites (M0).

Stage IIIB (T4, N0, M0): At least one tumor (any size) that has grown into a major branch of a large vein of the liver (the portal or hepatic vein) (T4). It has not spread to nearby lymph nodes (N0) or to distant sites (M0).

Stage IVA (Any T, N1, M0): A single tumor or many tumors of any size (Any T) that has spread to nearby lymph nodes (N1) but not distant sites (M0).

Stage IVB (Any T, Any N, M1): A single tumor or many tumors of any size (any T). It may have spread to nearby lymph nodes (any N). It has spread to distant organs such as the bones or lungs (M1).

How is liver cancer treated?

Treatment for liver cancer depends on many things, like your cancer stage, age, overall health, and testing results.

Your treatment may include some or all the following:

- Surgery.

- Local Treatments/Procedures.

- Radiation Therapy.

- Targeted Therapy.

- Immunotherapy.

- Chemotherapy.

- Clinical Trials.

Surgery

The type of surgery that you have depends on where your tumor is, the stage, and your overall health. Surgery is often only used if the cancer has not spread outside of your liver (metastasized).

There are two main types of surgery used for liver cancer:

- Partial hepatectomy: Part of the liver is removed (resected).

- Total hepatectomy: The whole liver is removed. This surgery is always followed by liver transplant surgery.

Talk with your provider about whether surgery will be a part of your treatment plan.

Local Treatments/Procedures

There are a few ways that liver cancer can be treated that only affect the cancer, called local treatments. These procedures can often be used if you are unable to have surgery. Some examples are:

- Radiofrequency Ablation (RFA): A probe is placed into the tumor. The probe has electrodes in it, which kill cancer cells. These electrodes emit high-energy heat. RFA can be done through the skin and does not always need an open operation. It is used on tumors smaller than 3 cm.

- Embolization: Most liver cancers get most of their blood supply through a blood vessel called the hepatic artery. By injecting chemotherapy through a catheter into the hepatic artery, also called chemoembolization, the blood flow through the artery is blocked and the blood supply to the tumor is stopped. It is first-line treatment for some types of tumors, and especially in patients with Child-Pugh class A liver disease.

- Radioembolization: Combines radiation therapy and embolization by using a radioactive isotope (yttrium y-90) to deliver radiation straight to the blood vessels that feed the tumor. Tiny glass or resin beads, filled with yttrium Y-90, are inserted. Once inside the blood vessels, the blood supply is to the tumor is blocked, but the healthy tissue around the tumor is spared.

- Ethanol (Alcohol) Injections: Ethanol (alcohol) is injected directly into tumors using small needles. The high concentration of ethanol used in these injections helps kill tumor cells. Only small tumors (2cm to 5 cm in size) can be treated with these injections. The injections can help when there are a few small tumors.

- Cryosurgery: Liquid nitrogen or argon is used to cool probes that are placed directly into the tumor. The probes freeze the cancer cells, killing them. Very little normal tissue is affected, so the risk of side effects from the treatment is less. However, it can only be used to treat tumors that can be seen by the naked eye (no more than 5 tumors that measure less than 5 cm) or by ultrasound. This is done as an operation in the OR.

Radiation Therapy

Radiation therapy is the use of high-energy x-rays to kill cancer cells. Radiation is not often used to treat liver cancer because it can damage the healthy parts of the liver. It can be used when other treatment options have not worked. Radiation may also be used to treat areas in the body where the cancer has spread and is causing side effects such as bone pain.

The most common type of radiation used for liver cancer is called stereotactic radiation (SBRT). Many different angles are used to focus the radiation at one small point. These beams combine to deliver high doses of radiation to the specific area of the liver tumor. This helps lessen how much of the liver receives radiation.

Targeted Therapy

Liver cancer may be treated with targeted therapies that focus on specific gene mutations or proteins in the tumor. Targeted therapies work by targeting something specific to a cancer cell, which helps kill cancer cells while affecting healthy cells less. Sometimes the “target” is found on a certain type of healthy cell and side effects can happen as a result.

Examples of targeted therapy medications used for liver cancer are sorafenib, lenvatinib, regorafenib, cabozantinib, bevacizumab, and ramucirumab.

Immunotherapy

Immunotherapy is the use of a person's own immune system to kill cancer cells.

Immunotherapy medications that may be used to treat this type of cancer are atezolizumab, durvalumab, pembrolizumab, nivolumab, ipilimumab, and tremelimumab.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy is the use of anti-cancer medications to kill cancer cells. Chemotherapy is mostly used when liver cancer has metastasized. It may also be used after surgery, to kill any cancer cells that may be left in the body. This is called adjuvant therapy. Most times, a combination of different medications are given together.

Chemotherapy medications that may be used to treat liver cancer are gemcitabine, oxaliplatin, cisplatin, doxorubicin (pegylated liposomal doxorubicin), 5-fluorouracil, capecitabine, and mitoxantrone.

Clinical Trials

You may be offered a clinical trial as part of your treatment plan. To find out more about current clinical trials, visit the OncoLink Clinical Trials Matching Service.

Making Treatment Decisions

Your care team will make sure you are included in choosing your treatment plan. This can be overwhelming as you may be given a few options to choose from. It feels like an emergency, but you can take a few weeks to meet with different providers and think about your options and what is best for you. This is a personal decision. Friends and family can help you talk through the options and the pros and cons of each, but they cannot make the decision for you. You need to be comfortable with your decision – this will help you move on to the next steps. If you ever have any questions or concerns, be sure to call your team.

You can learn more about liver cancer at OncoLink.org.